It’s a law in politics that there must always be a scandal; Ramses III had his harem conspiracy, Caligula and George III were both insane, Louis XVI had the Boehmer necklace. Today, now that there seems to have been no collusion between President Trump or his campaign with the Russians, the latest scandal has been pushed to the limelight—pornographic actress, Stormy Daniels.

Unlike the charges of Russian collusion, the allegations that Trump had a one-night stand with Daniels while married to the present Mrs. Trump seems likely. He doesn’t exactly have a clean record when it comes to being faithful in his marriages and the fact that his lawyer, Michael Cohen, gave Daniels $130,000 dollars just before the presidential election, seems suggestive.

“Stormgate” (we may as well call it that) is not the first time that a president’s private life has been scrutinized. Jefferson was eviscerated in the press when James Callender first slip the rumors of Sally Hemmings; in the election of 1884, it came out that Grover Cleveland had fathered an illegitimate child with a woman named Maria Halpin. These stories raise the question: Does character matter in public officials and, if it does, how much is it worth?

The short and sweet answer is, Yes—character does matter. George Washington said, “Good moral character is the first essential in a man.” Washington was not just expressing a truth for the 18th century or a simple truism of his time but was stating in his straightforward way a universal principle. For an example of what constitutes a good, moral character, we can look at the Scout Law, the set of twelve principles by which every Scout swears to live by—trustworthiness, loyalty, friendliness, helpfulness, friendliness, courteousness, kindliness, obedience, cheerfulness, thriftiness, bravery, cleanliness and reverence. These words hold a lot more meaning than they first appear. A few months before his death, John Wayne was the guest of honor at a dinner hosted by the Boy Scouts of America’s Los Angles Area Council which had just named the John Wayne Outpost Camp after the actor and American legend. In his speech, Wayne reflected on the Scout Law. Some of the observations he made were:

Loyal—the very word is life itself, for without loyalty we have no love of person or country.

Obedient—Start at home, practice on your family, enlarge it to your friends, share it with humanity.

Clean—soap and water help a lot on the outside. But it’s the inside that counts and don’t ever forget it.

Reverence—Believe in anything that you want to believe in but keep God at the top of it. With Him, life can be a beautiful experience. Without Him, you are just bidding time.

Good moral character, following the Scout Law means, at its heart, that the good man and the good woman think of others before themselves; is true to his connections and bonds, whether they be to his family, to his neighbors, or to his country; that he lives by a code of ethics that conforms to reason and the universal law which the Roman senator, Cicero, spoke; and that he is faithful to those who have legitimate authority over him. In other words, they are the principles that turn boys and girls into men and women.

My grandfather was a prime example of this. A farmer in rural Missouri for most of his life, he was never that rich and he never held political office on any level but he cast a giant shadow because of his character. He was the embodiment of the phrase, “His word is his bond,” since if he said anything people knew that it would be done. Whenever anyone was stuck in the mud after a rain, Grandpa would pull them out with the tractor, no matter what time it was. It’s been said that a man can be partially judged; when he died in 2012, the church was overflowing with people.

The importance of good, moral character, particularly as we have outlined with the twelve planks of the Scout Law, can be seen by a simple thought experiment: Imagine a world or society where the principles of the Scout Law were not taught, that instead of teaching the value of honesty, people were taught that it didn’t really matter if one was honest or dishonest; rudeness was just as good as courteousness; betrayal was just as valid as loyalty; and it didn’t matter if one was obedient to lawful authority or not. It doesn’t take much imagination to realize that a world created by our thought experiment would not only be poor one but a dangerous one, a world where we could never be certain if someone was lying to us or not, where we could never know for sure if our orders were carried out or not (say if one was a small business owner with five employees), where, as Wayne pointed out in his speech, we would never be fully committed to giving our time, help, or love to anyone or anything since there would be no assurance that they wouldn’t turn around and stab us in the back. It would be a miserable world, a cold world and an unfree world.

With the allegations of Stormy Daniels, some people have come out to say that they don’t matter, even if they turn out to be true. Ann Coulter, at one point, said that you don’t ask the fireman who carries you out of the burning building if he went to church that Sunday and others have said that Trump was elected to be president and not a pastor. In a sense, that’s true. Trump was elected to the White House because enough Americans believed that the country was going down a very bad path. Everyone knew about his past and his two other affairs but voted for him because of his ideas and the policies he said that he would deliver. Trump was elected to be our president and not our pastor.

At the same time, that sentiment is not honest and obfuscates the question. Of course the presidency is not a pastorship; the United States is not a theocracy. But no president has ever confused his role in the executive branch with being a pastor. It’s true that George Washington and John Adams called for the states and the churches to set days aside for fasting and prayer to ask for God’s help, but these were calls to actions and not sermons and neither Washington nor Adams gave a sermon on these days. At the same time, though, past presidents did strive to lead a moral life; Washington lived by his 54 rules of civility, Adams, in the twilight of his life, wrote a letter to his children declaring that he had always strived to live morally (one of the specific things Adams mentioned was that he had not had any affairs and/or illegitimate children), Abraham Lincoln, even before his religious “conversion” during the Civil War, lived a moral life. Many of these men sought to develop good, moral characters in spite of their weaknesses; Washington had a furious temper which he always guarded against; Adams could be vain and crabby; Lincoln was subject to bouts of severe depression. What is more, many past presidents developed and kept a good, moral character, jot only because it was good in itself, but because they knew that they were leaders and that people looked at them as such. It’s no secret that Thomas Jefferson’s religious sentiments were unorthodox, especially for 19th century America. And yet, as president, he attended services every week at the House of Representatives. When asked why he would do this, Jefferson answered that the president had to set a good example.

Asking which is more important in a president—policy ideas and results or character—is the wrong question, similar to asking if water or food is more important for life. Both are equally important and are needed. Sometimes a candidate only comes with one or the other and then a choice has to be made. That is understandable since we do not live in a perfect world. But that is no reason for wanting both—good ideas and good morals—in our leaders. If we hold our spouse, our parents, our siblings, our friends, our co-workers to a certain standard, why shouldn’t we do the same thing for our leaders? Especially in a republic, our leaders are seen (or are supposed to be seen) not as demi-gods, destined to wield power; that can only come through History. They are, instead, supposed to be seen as one of us, given the people’s trust for a time before retiring (or being freed as Benjamin Franklin put it) back to being a private citizen. Don’t we want the best as our leaders? Shouldn’t we be honest and, when our leaders falter, point it out and encourage/hope that they will improve?

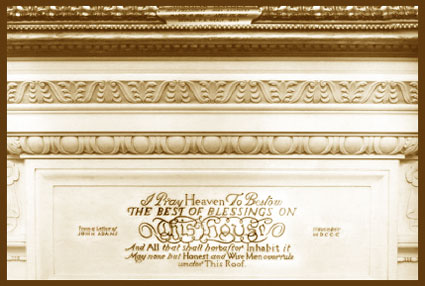

In a letter to Abigail, John Adams, writing of the newly built White House, “I pray Heaven to bestow the best of Blessings on this House and all that shall hereafter inhabit it. May none but honest and wise Men ever rule under this roof.” It’s a prayer that we could all repeat, regardless of who sits in the Oval Office.